Lava Falls High

A Season For Brotherhood

7 boats littered with gear for 21 days off the grid. 14 strangers. 280 miles of history, wilderness, rapids and flatwater. That was the proposition.

Going in, I knew Erik would bring beer, and knowing him, it was going to be good beer.

I knew I'd love the Grand Canyon. After nearly a decade of working as a part-time fly fishing guide and a full-time REI copywriter, I was ready for some unstructured time.

My brother, a former whitewater guide (vocation and avocation), said he was mostly sure the group would come together and would actually launch at Lee's Ferry at the appointed date. The permit seemed good. Group leader looks like he's got his shit together, so that's good. Seemed like we had a few experienced oarsmen, which was also good. I knew my brother. He knew one more guy on the trip. Group dynamics were anybody's guess, but, ya know, things tend to work themselves out. Should be good.

Life speeds up, and you don't get time with important people in your life who matter. So most of the decision to go was clear. The other part, that niggling part that has to do with Class V rapids and putting your safety in a small community of strangers and possibly contracting a spectacularly brutal form of stomach flu people tend to get on these types of trips was, well ... turns out not that many people actually die in the Grand Canyon. Surprisingly few, given the number of annual visitors. If they go, it's not while rafting, but while swimming and trying to cool off. As I was going to pilot an 18 ft. self-bailing SOTAR, a high-flotation tank, the odds were in my favor. Seems good.

Loading up the boats at Lee's Ferry

I trusted my ability to read water and my skills as a guide if I needed them. I knew my brother probably wouldn't let anything severely bad go down if he could help it. I know I'm never going to get three weeks of river time again until I retire. The rest? What good is certainty, anyway?

Lee's Ferry, First Light

I have a strange notion when it comes to being outside. It starts with motivation. Why do you go outside? When you do, why do you do what you do? More simply put—what drives you outdoors?

For me, it's fly fishing. I grew up chasing fish in my backyard in Denver, Colorado. One of my best memories as a kid involves my Dad dropping me off at some local ponds while he ran errands, then coming to pick me up after I terrorized some panfish. I'm pretty sure I still have the first fly I tied that caught a bluegill somewhere in a drawer. When I realized that the slow-moving portion of the South Platte near those ponds also held fish, and even the occasional trout,something powerful clicked. From that point on, errands were no longer a reason for boredom. Thanks, Dad!

Deer Falls

The habit grew from there. From ponds, to Waterton Canyon, to Deckers, then Cheeseman, and the Blue, then Flaming Gorge,UT, and the Rio Grande near Creede, CO and beyond. I followed a path that ultimately lead me to steelhead and the waters of the Pacific Northwest. Nothing will ever get me up in the morning as quickly as a trip to chase fish. It's what drives me outdoors.

What drives you? For friends Matt and Court, it is clearly Washington powder. For REI buddy Joe, it is the top of the mountain, and the process that takes you there. For my brother Erik, it's the rock of the canyon, the river that carves it, and the way time moves on the water. And although I dabble in all these disciplines, nothing will ever have the pull of a wild fish in pristine water. Or so I thought.

What could go wrong, seriously?

There are many extremely detailed accounts of descending the Colorado to be found, but unless you have actually run the river or something like it, the play-by-play can be pretty boring. So here are a couple lessons from the trip.

Charging is more fun. This one was clearly articulated by my older and more experienced brother when I was seeking advice about the Roaring 20s, a quick series of fairly mellow rapids that don't pose much of a threat to an 18 ft. SOTAR, at least not at the water levels we were running. Seemed like sound advice, so I plugged us into the throat of the wave train and kept firm hold of the oars. I was far enough along on the trip to gain some confidence, and it was pretty fun getting blasted by towering waves. A jet of water pressed my sunglasses into my face so hard I thought they might break, then caused my lenses to fog up instantly during the gnarliest part of the drop. Clarity is overrated. It was really, really fun, though my passenger might disagree.

You will never have a more harmonious perception of time passing in your life than you will on a river trip. It's part of the reason I still love to do an overnight float anytime I can. As soon as you launch, the rhythms of the natural world dictate your actions. Given some experience, you learn that it's really no use to push against those rhythms. Sure, you can impose your own agenda, but often it just makes you tired and cranky when the conditions conflict. It sets you on a different pace, and your thoughts slow down. It's much easier to give important things the attention they deserve. I find that even a quick overnight float has a beneficial effect on me. It's sort of like taking your mind to the cleaners.

Floating the Grand Canyon is an exponential amplification of river time. Not only must you commit to a significant period of downtime to experience it, but also you are floating through an expansive record of the history of the planet. Early in the float, you come through the Upper Granite Gorge, and the aesthetics change even for someone who knows nothing about geology. Ancient rock, appropriately dubbed Zoroaster and Vishnu, change the feel almost instantly. These granite and schist formations are 1.7 billion years old, a figure you have a lot of time to try and conceptualize while you float. It's the basement of the world, exposed to a moment of your puny human lifetime. It really doesn't matter whether you perceive it at all. You don't really matter all that much when compared to the processes that created the canyon around you. Everything you've ever known, for that matter, is infinitesimally tiny compared to what gave rise to that rock. And you get to experience it in the best way our American culture can come up with, in a place specifically protected so that you can gain some perspective.

Near Nankoweep Grainary - E.Oerter Photo

It's heady stuff. You get soaked in it. It becomes, like your smartphone in that other life at home, a fixture in the background of what's going on. For much of the trip, the grandeur can be monotonous. Just another day in paradise. You've gotta think about your boat, the gear, who's on groover duty, where is that hand soap? Who's got the freaking HAND SOAP?! What about mayo? I need the HAND SOAP GODDAMMIT!

But just take a second to look around and there it is. Limitless time and unbounded reality that will go on for millennia with or without our help. River time plus the in-your-face geology makes it unique. There is no other place like it for the simple reason that it really changes how you think about time.

Lesson Three?

" We are a very small community. "

-Quote attributed to D.P. Al-Sadr, wise guy and keeper of the wax

Settling in for the evening at Ledges Camp

Half of the fun of the trip is getting to know the group. Granted, I typify the type of person who's prone to falling off the grid for three weeks at a time; independent, atypical and introverted. And I have a pretty strong antisocial streak when trout are to be had. Hey, I like my solitude!

But the unexpected thing about spending time with a small group of people for an extended period of time is how quickly the defenses come down and you get to the very important business of having a great time. Sure, people get rubbed the wrong way and there are conflicts. Important aspects of the trip don't get done right. For instance, our group was horrible at getting out of camp in the morning, and it prevented us from doing some cool side trips and set us behind schedule. We also took awhile to figure out how to get everyone working together to get the boats unloaded, but eventually we managed. These are all real downsides when you are in the moment and things aren't going right.

Despite these frustrations, however, we become dependent on each other for the necessities of daily life in a way that humans virtually never experience anymore, and it's not necessarily a bad thing. This includes food, water, a groover, and saving your teammates' skin if they come through a rapid with the wrong side up. Everyone steps up when we're so dependent on one another. The campfire conversations at the end of a successful day are easy and engaging. Cooking together is super fun, and eating together is super fun. And when everyone makes it through a tough rapid safely, it's time to crack a beer and enjoy the moment in a way that I'd argue is pretty much impossible in the normal flow of daily life. That brings me to Lava.

Cactus Below Throne Room

You encounter Lava Falls beyond the half-way point in the trip, at least as the miles go. At this point your group has hopefully found its groove, because if you haven't it's probably not there. Lucky for us, our challenges were routinely overcome, if by a thin margin.

On day two or three we had to move each of our boats off a dry beach in order to launch. It was hard work, but we got it done in a hurry. That was the first time I noticed that we actually accomplished something as a group, and it was a good start. Later that week, we blazed through some exciting rapids with no major mishaps. Although rafts flipped a couple times, we didn't lose any key gear, and it offered a lot of experience for those new to the process.Nobody had been seriously injured or contracted norovirus, a gastro-intestinal plague that tends to happen in the canyon. And although we couldn't seem to get out of camp before 10 AM, the side trips were spectacular. We explored Havasu Canyon, one of the scenic highlights distinguished by the azure waters of Havasu Creek. There, we met and compared notes with another group, and realized we weren't doing so bad. A few days before Havasu, we hiked up to the Throne Room above Deer Creek. It was one of the best layover days, at least in my book. Before that, good times were had at Elves' Chasm, one of the most enchanting spots on the planet, especially when you haven't felt the fresh push of clean water over your skin in days. We'd made it through Horn, Hance, Granite, Hermit, Crystal and Bedrock rapids relatively unscathed, though they gave our IKer's a workout. Nobody from our group had hiked out at and subsequently been murdered by hostile Arizona natives at Separation Canyon, at least not to our knowledge. Lava Falls was coming up, but not for another day. And that morning, if memory serves, someone actually found the freakin' hand soap.

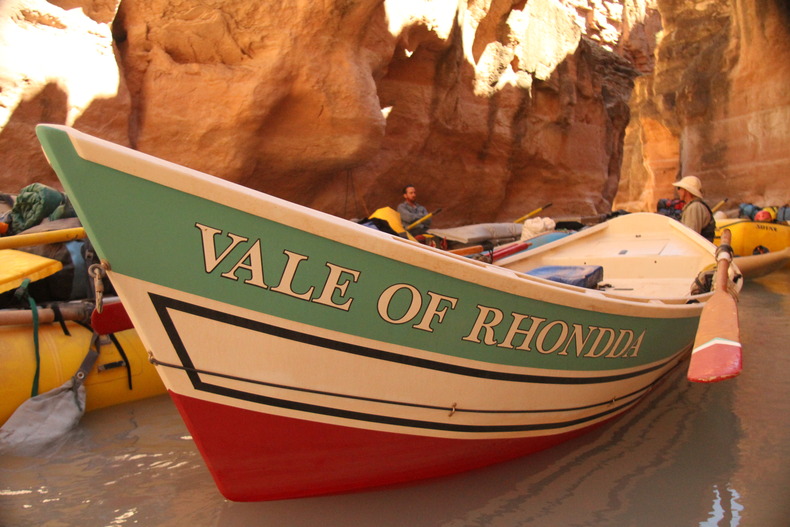

Chatting with a Dory group Anchored at Havasu Creek

So when we coasted into the last miles before that big drop, there was a lot to lose. Lava isn't just a rapid. It's more of a mental marker, an indication that you've gotten through the toughest part of the trip. Before Lava, the most inexperienced boatman in the group has a great chance of flipping the boat. That was me, by the way, in the groover boat; and nobody wants the groover boat to flip. I'll let you draw your own conclusions with that mental image.

Anything can happen in the maw of the beast. It's the most difficult 20 seconds of the trip. If you don't choose your line correctly, insanely powerful flows toss your boat as if it were weightless. The river carved the canyon, and it can make short work of you and your little rubber raft. You have to know how to follow it. There are plenty of ways to mess up in the thick of the rapid, but really there's only one really bad way, and it's called the Ledge Hole. In the middle of the river on the left side, there's a huge pour-over the size of a bus. If you get anywhere near it, the force of the water can snap your oars, destroy your frame and propel you into the depths of the water where your fate is anyone's guess. It's bad news. Whatever happens, don't hit the Ledge Hole.

To raise the stakes, one of my passengers was suffering a severe bout of unidentifiable canyon funk. Normally he'd be running his inflatable kayak, drinking beer, joking around and having a contagiously good time. Sickness happens in the canyon, however, and his number was up. Alternatively shivering and overheating, he could not regulate his temperature and was in no shape to walk around the rapid. If we decided it was too dangerous to run Lava, someone would have to support him step-by-step through the lengthy hike, and we were already pretty far behind schedule. We decided to make him comfortable in a dry suit, rigged a place to sit with plenty of strong handles in the gear pile in the back of the raft, and instructed me on the best line possible so he wouldn't have to swim. I'd go late in the order so if something happened, downstream boats could pull us out of the water. A couple sweeper boats would follow me, also a measure of insurance.

Lava Falls from the Scouting Point, Ledge Hole Center Left - E.Oerter Photo

For those who have never run a trip like this, it's important to realize that you actually park your boats, get onto shore, and go look at the river before you run a dangerous rapid. The most experienced boatman typically calls out the biggest dangers of the rapid, sketches a route and draws up a plan. It's an extremely important process because things can happen really quickly when you're plugged in to big water. It just takes one wave to spin your boat and disorient you. Without a game plan, things can go to hell in a hurry.

There's a pleasurable anxiety to the process. One moment, you are above the rapid, calmly dissecting its features and sizing up your potential path. Minutes later in the rapid, you are completely absorbed by the task at hand, reacting to pure chaos and split-second events. In between, there's a beat of quiet just before you drop in, where you commit to your line and all that follows. It's an exquisite moment of pure concentration. At Lava, there's a grace note of pure terror.

I ran over the reference points for my line again and again in my head, and when it was time, I launched us into Lava. Erik, having struck a Faustian bargain some years earlier, had rowed down on a golden line and hardly gotten wet. I knew he was waiting downstream watching. And here comes my reference, river right, the big rock that starts that eddy with a bit of a foam line. Start moving left to keep you off the right wall, but not too far. Picking up speed now, just a few oar strokes left. Am I where I want to be before we drop into the first big wave? As a matter of fact … OH SHIT, I AM TOO FAR LEFT AND GOING RIGHT INTO THE LEDGE HOLE! Pull right, pull right, PULL RIGHT!

Spiked adrenaline supplied freaky strength, and by the time the first wave hit I had the raft positioned as best I could. We were in it. If the raft slid into the Ledge Hole, it would be pretty obvious I picked a bad line as the raft flipped. At that point there was nothing further I could do except hold on to the oars and react. But the big hit never came. The line was good. Lava spit us out in seconds, pushing a couple big splashes over the bow and giving me one helluva rush. We had made it out. Passengers were aboard, intact, and smiling. But wait, had I said, “Oh Shit” out loud? Man, I gotta keep tabs on that internal dialog.

Everyone made it through safely that day, and we celebrated at Tequila Beach, the namesake of the pullout directly below Lava Falls. Although there were still 100 mi. left to row and some sleeper rapids that can catch you off guard, the group let out a collective sigh of relief as the shots flowed.

Nothing Really Serious Happens After Lava - Travertine Falls Group Shot

Happy Hour in the Canyon

Certainly, there were other highlights to the rest of the trip. Pumpkin Spring and the Manhole. Diamond Peak and Travertine Canyon. Talking a look at Pierce Canyon rapid after takeout and then charging straight to Vegas, baby! Oh, and did I mention strapping our rafts together on the last night and floating 60 mi. in moonlight to make the takeout at Pierce Ferry the next day? Watching the canyon pass by under bright moonlight was surreal.

Rapid Below Pierce Ferry - Crazy Big Water - E. Oerter Photo

Nothing comes close in memory to that moment after Lava, however. The group had gelled; we had run the most dangerous part of the river and the remnants of our former lives were washed away somewhere upstream, at least as long as we were in the Canyon. At the beginning we were nothing but a group of strangers, but by Lava we had become a small community. It was important that I ran that rapid well, and it was important that I got to see the canyon with Erik, my brother.

Me and Erik in the Canyon

There's no use in sugar-coating it: the trip was not easy for me. Even under the best of circumstances, running your own raft down the Grand Canyon is probably not something I'd put in the easy category. I'd like to run it again, if only to be more present during portions of the trip where I was too tired to do much but sit there and stare. I would have liked to have taken more side trips, and I really wish I hadn't gotten a brutal cold for the first half which basically sent me right to bed as soon as I got to camp for the first 10 days or so. I wish I had worked on a little more background info to understand the significance of what I was doing. I would have liked to have learned more about the geology, especially before I went.

But in the grand scheme of things, being prepped for a trip of a lifetime isn't as important as being present when you're there. That's the gift of the trip like that: presence. It gets addictive.

A shift in perspective happens after you run 280 mi. down ancient canyons a mile deep. Maybe you don't notice at first, but the canyon and the river change how you approach things. Afterwards, it's hard to look at anything significant, whether man-made or naturally crafted, without a certain degree of skepticism for its origins and longevity. And it's tough to value any significance, no matter how celebrated, in relation to the scale of Grand Canyon.

Yes, the scenic stuff you've regularly used for inspiration loses that lovin' feeling. The Yakima canyon, a former store of majesty and wonder, looked a lot less majestic when I floated it in March. In fact, it looked rather tame and ditchlike. Fast water that used to give me pause, especially in my Packraft (The Green Machine!), no longer had any teeth. Turns out, when you've run a waterfall with a strong member of your team strapped to the back, delirious, shaking, and in no shape for a swim in the most dangerous rapid in the river, there's not much that's going to phase you. Just don't say "Oh SHIT" too loud when you think you've miscalculated your line on Lava. It turns out that freaks out your passengers, even when you course correct in time.

Ultimately, a trip down the Grand Canyon can mean whatever you like it to. It can be a vacation, a special occasion with family or friends, a geology lesson, a shelter from everyday life, an experiment in group dynamics, or something else entirely. Whatever it may be to those who undertake the journey, one thing is sure—it's unlike any other experience you'll ever have. Protect it, protect the place the makes it possible, and celebrate the culture that makes it happen.

And please, will someone find the FREAKING HAND SOAP!?

Group Shot at Redwall Cavern - Anna Chiacchella Photo

More Photos Here https://goo.gl/photos/s2uZQJLrvgeKqmkc6

A Season For Steelhead, Powder, Waves and Bonefish